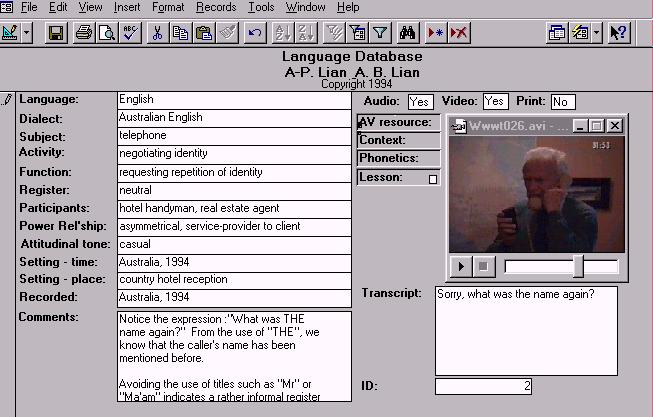

Screen Layout for MMBase (Audiovisual database)

Introduction

This paper proposes an intellectual framework for the development of

foreign/second language learning environments. A central premise here is

the conceptualisation of learners as social subjects with "dispositions

to think and act in certain ways rooted in [their] discursive histories"

(Lantolf, 1995, pp. 116-117). The question which the paper attempts to

tackle is that of the place of learners as individuals in an environment

where the goal is to sensitise them to the systematicities of the target

language systems. The framework proposed seeks to suggest ways of achieving

this goal without necessarily subjecting learners to pre-determined and

pre-organised procedures which claim their legitimacy either in teachers’

experience or in theoretical models of acquisition.

The general direction which the article follows revolves around the issue of dealing with the unpredictable perceptions of heterogeneous learners: an aspect of pedagogy which remains ignored in environments where concern with Abalanced@ lessons and controlled progressions from "easy" to "difficult" based on features of formal systems eclipses concern for learners as organisers of the socially-based schemes which they construct. Thus the article argues for an environment where the need to question and discover drives the learners’ explorations of the relationships between the language and the social practices which have shaped its place and functioning in speech communities i.e. language in authentic contexts (Hymes 1996, p. 30).

In the proposed environment, the task of the learner shifts away from that of putting together the pieces of language, i.e. knowledge, which have been revealed gradually whenever the teacher considered it was appropriate to do so. Given the differences between people, teachers can never know what pieces of knowledge to give and when to provide them as it is not possible to know the nature of the "what" and the exact moment of the "when". Only the learner is able to decide, and not always in a conscious manner, the required "what" and "when" as it can only be the learner who is ultimately in charge of relating to one another the various pieces of information available and thus to construct meanings.

A focus on the learner as organiser implies the necessity to hand over control of the learning steps to the learners and requires from the teacher to take a backseat in this process. Thus, while the task of the learner is to coordinate cultural practices of target speech communities as well as to perceive the coordination of these practices (Bourdieu, 1995, p. 59), the task of the teacher is to help learners achieve this in ways which do not distort the principles of that coordinating through attempts directed at cutting practices off from their real conditions of existence (cf. Lian & Mestre, 1985).

Thus the task of a language-learning environment is to move away from conceptualisation of the learning process as that of recording of knowledge passed on from the knower to the learner, or from an expert to a naive person. Rather, its task is to meet the challenges implicit in the view that the process of learning is that of relating the old to the new: a genuinely individualised understanding of learning directed toward facilitating development of principles for generating appropriate cultural behaviours. In practical terms, this requirement leads to a necessity to create conditions where the learner is given access to a multitude of devices to facilitate the linking and organising of information. This may be achieved through exploration of systematicities of communicative practices in ways which allow learners to investigate the ways in which these may combine or integrate with one another (cf. Guberina, 1972, p. 29).

The pages which follow will

Anecdote 1 (with apologies to the TV series Kung Fu)

In the gardens of a Shao-Lin Temple, an old blind monk and his apprentice

(Grasshopper) are walking.

Grasshopper: Nothing Master!

Shao-Lin Monk: Grasshopper. Do you not hear the beating of your heart and the rush of the wind in the trees?

Grasshopper: Yes master. I am now deafened by the roar of my heartbeat and the tornado in the trees, etc., etc.! Master, How is it that you can hear such things?

Shao-Lin Monk: Grasshopper. How is it that you cannot?

But help is at hand. Here comes Dr G.

Dr G.: Now, Andrew, what do you see when you look for Halley’s comet?

Andrew: Stars.

Dr G.: Good. Do you know any stars? Do you know what the Southern Cross looks like?

Andrew: Ummm, not really. I was always told to look for it but you know what it’s like... and then everybody starts to laugh at me.

Dr G.: OK. Well, if you look right above you, can you see a line of stars all in a row? That’s the tail of the Southern Cross.

Andrew: I am really really sorry, but all I see is stars.

Dr G.: OK. Ummm, let’s try something else. Here is a cardboard tube. Now I’ll cut some slits in its sides, but don’t worry about that right now. I will point the tube to Halley’s comet, and you can look at it through the tube. That way you will get to know what it looks like.

Andrew looks.

Andrew: Good grief! Do you mean to say that’s what Halley’s comet looks like? I expected something really bright. impressive...

Dr G.: Sorry to disappoint you. Now take your eye away from the cardboard tube and see if you can spot the comet.

Andrew: Oh dear, I’ve lost it again. I must be so stupid...

Dr G.: Back to the cardboard tube. Now can you see it once again?

Andrew: Yes

Dr G: All right. Well... with your eyes still on the comet, open up the tube by pulling back a little on the slits in the cardboard. Can you still see it?

Andrew: Yes.

Dr G.: Good. With your eye still looking through the tube look around the comet at the new bits of sky which you can see. Can you still make out the comet?

Andrew: Yes.

Dr G.: All right. Keep looking around and opening up the tube more and more. Can you still see it?

Andrew: Yes.

Dr G.: Well now you can probably remove the tube altogether. But don’t forget to keep your eyes on the comet.

Andrew: Okay. I can still see the comet.

Dr G.: Turn your back on the comet and look at other parts of the sky. Now look up. Can you still spot it?

Dr G: Yes. Oh yes. It’s really obvious now. In fact that’s almost all I can see in the sky. Can we do the same with the Southern Cross?

Both stories tell of an individual faced with the inability to perceive something which presents no difficulties to someone else. The first story tells of a person with a problem in auditory perception while the other tells of someone with a problem of visual perception.

Both problems are solved through the intervention of a helper who develops in each of them an awareness of the things to look for. The helpers generate sets of mechanisms determined fundamentally by the person in difficulty to transform a physical phenomenon, which is indisputably present but unrecognised (the sound waves in fact hit Grasshopper's eardrums and the light from Halley’s comet in fact hits Andrew’s retina), into a personal reality for each of our heroes. After the helper’s intervention, the status of each phenomenon has changed from one of total absence within the individual’s internal system to something which is now part of it. In short, the meaningless has become meaningful. This was achieved by bringing about a change in the process of selection that each individual carries within him or her and which makes him or her decide what to exclude and, therefore, what to include into the store of relationships which matter to them at a personal level.

In the case of Grasshopper, his heartbeat and the wind, though he could obviously hear both, and was in fact constantly hearing them, were meaningless in the context of his organisational systems and therefore did not enter into the class of "things that mattered". As a consequence they belonged to the class of "things that did not matter" and "things that do not matter" are rejected by our perceptual systems. To quote Petar Guberina, "Structure comes into being by selecting certain elements while eliminating the others" (Guberina 1972, p. 206). This is echoed by Jakobson who, when speaking of development of the child’s phonological system, asserts that the rich chirping of the child gives way to phonological restriction.

In the second example, asserting the existence of Halley’s comet, attempting to describe it or otherwise talking about it was not sufficient to bring that object into the person’s perceptual world. A special procedure was necessary. Fundamental to that procedure was the creation of a relationship between the person and the object through an approach which did a number of interesting things:

Critical issues

The world is made up of individuals who are endowed with their own

personal organisational systems. People are organisers i.e. for all aspects

of their lives people select the things which matter and reject those which

do not. Without such a form of organisation, people could simply not function.

(Guberina 1972, p. 75; Bourdieu 1995, pp. 60-61)

Take the case of autistic people. One theory of autism suggests that autistic people have no organising mechanism to help them sort out, unconsciously, which of the myriad of signals to which they are exposed matter and which do not. They seem to suffer from a form of overload. Unable to select from this endless bombardment of information, all signals are equally meaningful and therefore meaningless. The only possible outcome is, essentially, a form of paralysis. To solve this problem, Temple Grandin, a Professor of Animal Husbandry at Colorado State University, who is autistic, developed a special procedure. It is a form of sensory deprivation where she places herself in a special device which prevents her from moving and which limits the amount of information (i.e. physical signals) to which she is exposed both from within and outside her body. She appears to have enough organisational ability in place to cope with the reduced input to stabilise herself, rest and further develop her organising systems. (for further details, cf. Grandin, T. 1996).

In the case of people with no organisational difficulty, each individual’s cultural and experiential history generates vectors of organisation or, if one prefers, general trends of organisation.

While it may be possible to identify general trends (e.g. French speakers will make literary allusions more commonly than English speakers), the exact organisation of the schemata or principles which determine each person’s way of structuring is individual and therefore beyond the bounds of external observation, at least so far. We as teachers, friends or other human beings, simply cannot know the detail of what is going on inside someone’s brain.

These phenomena of organisation and selection can be understood through the use of the filter metaphor which P. Guberina and the verbo-tonalists (e.g. Guberina 1972; Renard 1978; Lian 1980, Lian & Joy 1981, Lian & Joy 1982) have developed (originally based on Trubetzkoy’s notion of the phonological sieve: a mechanism for keeping sounds which are recognised and rejecting those which are not). The concept is generalisable and applicable to the context of learning in general and, indeed, to everyday living. The theory postulates that the filter constantly mediates perception on the basis of each individual’s past experiences and interactions with the world (thus having a clear social dimension) and helps to determine those things in life which matter (including linguistic features) while rejecting those which do not. The filter is fully dynamic and new experiences constantly change the characteristics of that filter.

A similar concept has been developed by P. Bourdieu in the context of his work in the area of cultural practices. He calls this the habitus.

This line of argumentation, because it relies on the presence of highly personal perceptual mechanisms, implies that people experience different kinds of difficulties in learning a language and that corrective intervention needs to be adaptable to the learner. In other words, individualisation is crucial. It is not a luxury, but a necessity.

Furthermore, the example of Andrew’s difficulties with Halley’s comet points to the need for replacing things which are perceived in non-authentic settings, in this case the brightness and configuration of the comet, back into the complexity of the globality (or authenticity) in which they are always embedded, from which they are not independent and which hides them from the uninitiated.

This kind of framework will require the development of educational environments where, contrary to research which seeks to discover conditions for facilitating the transmission of information, the focus will be on a concern with the learner as organiser of communicative systems through the practice of participation, observation and reflection (Hymes 1996, p. 9). As a result, emphasis should be placed on the creation of conditions allowing learners to organise effectively and to infer for themselves the kinds of principles which will enable them to control all communicative systems at once. This implies rejection of approaches dealing essentially with systems extracted from the rest of the communicative systems and treated as self-contained objects able to be described and treated as isolated pieces of information to be passed on by the teachers to the learners. In real life, people have to deal simultaneously with all systems. They have to process all systems simultaneously and therefore, in the context of language learning, learners need to be exposed to all systems simultaneously. This necessarily calls for the use of authentic resources (as non-authentic resources lack some of the systems). This requirement stems from the recognition that text production is the result of strategic assessment of all perceived aspects of discursive situations (Freadman 1994). Denying access to the complexity of the globality (i.e. the authenticity of the conditions) is to take the learner away from the ‘linguistic market’ (Luke 1992 p. 126) where realisation of practical purposes, necessitated through acts of communicative practices, is the deciding factor in the process of learning social appropriacy.

Implementation considerations

A system such as the one described implies the ability for people,

either singly or in groups, to do different things at different times,

and attacks in a fundamental way the standard notion of "classroom" as

the privileged place for teaching and learning and as a place for synchronous

activity. In turn, this also attacks the concept of fixed teaching materials

supporting a pre-determined teaching programme. If different people do

different things at the same time they will need to have access to different

materials for different purposes. Thus the standard pre-programmed textbook

would disappear and would need to be replaced by something like sets of

organised resources. These could take the form of on-line databases of

authentic materials (cf. .Lian & Mestre, 1985; Lian, A. B., 1996).

Furthermore, if persons are to work independently and at their own pace they will need to be provided with support suitable for interacting with materials in personally useful ways. Help from a teacher or other knowledgeable person may not always be at hand. It should also be added that not all teachers will know all of the answers to all of the learners’ difficulties. Research into appropriately-supportive environments must therefore become a key area of language-teaching and learning research.

Environments of the kind just outlined would benefit considerably from the use of modern technology. In fact, given the diversity of tasks, demands and information requirements the only genuine option may be to base them heavily on such technology.

Research into the characteristics and practical implementation of such environments has begun at James Cook University. Concurrent with this initiative, however, has been the development of a number of component-tools consistent with the theoretical characteristics of these environments and which will help to identify worthwhile research directions while providing support for language-learning in the short-term. Brief descriptions of some of these systems now follow (complete descriptions are beyond the scope of this paper):

MMBase: Audiovisual database (Lian, A. B. 1996)

All categories are searchable and each can be related to the others in arbitrary ways according to the wishes of learners. The system can also provide links to specific lessons where these have been made available.

For instance, learners who need to prepare "A day on French television" might wish to examine a French television advertisement about dental plaque-removers. They can search according to the criteria of French language, the activity of advertising and a function containing the word "plaque". By clicking on the words AV resource, they are then able to see the advertisement and to read the transcript and comments relating to the interaction which they have just witnessed. If they wish to, they can compare the advertisements they find with similar advertisements in other languages.

Other interesting studies which database systems such as this might facilitate include the possibility of cross-linguistic and cross-cultural comparisons of a broader kind e.g. How does English advertising work as opposed to Chinese advertising? Alternatively, it can also be a valuable tool for answering more sociologically-based questions such as: "How are women represented in the advertising discourses of Chinese, French, German and Japanese cultures?". Information can be quickly retrieved and contrasted. Imagination and need will ultimately determine the range of possible uses of systems such as these.

In other words, the database is a kind of audiovisual dictionary which gives learners accurate, instant access to relevant audio and video information. By cutting down on the drudgery of information retrieval and management the learners' environment is enriched considerably.

It is expected that in 1997, a prototype version of this database will be made available for use across the Internet through the use of Web database systems such as Cold Fusion (a product of Allaire corporation) and streaming audio and video systems such as RealAudio and RealVideo (a product of Progressive Networks). (The above is a modified version of a description published in Lian, A-P. and Lian, A. B. 1996.; cf. also Lian & Mestre 1983).

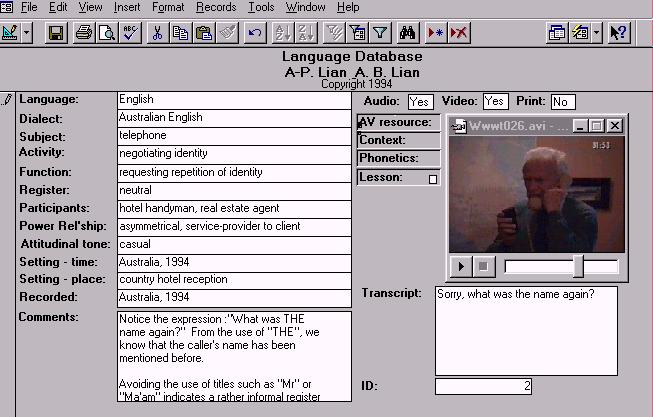

MMBrowse: a multimedia browser (Lian 1993, Lian & Lian 1996)

MMBrowse is a system which combines the development of listening comprehension with text-exploration and awareness-raising. It is designed to enable learners to discover, observe and reflect (Hymes 1996) while varying the processing load in many different ways.

MMBrowse is a multimedia browser designed to develop listening comprehension skills through a self-study approach based on the exploration of authentic audio and/or video text leading to the development of an awareness of the critical features of authentic text.

An audio or video file is recorded in digital form onto a computer's hard disk or on a CD-ROM. Students are then provided with a written transcript of the passage where each letter in every word has been replaced with an asterisk (*). The learner's task is to discover the words underneath the asterisks, to gain an understanding of the passage and to come to grips with the features of the text.

The technique of replacing letters with asterisks is a load-reduction mechanism which provides learners with clues as to the shape of the words they should expect without actually eliminating the challenge of discovering the words of the text.

The system allows for the interactive exploration of the text by enabling learners to:

Use of MMBrowse is not limited to foreign/second language learning but, because of its ability to link sound or sound and pictures to speech events, the system could be used for analysing many phenomena such as the relationship between speech and gesture.

A feature of this program is that it contains an authoring system which reduces considerably the burden of lesson-writing, thus allowing teachers in the field to develop their own materials with relative ease." (for further details, cf. Lian 1993) (The above is a modified version of a description published in Lian, A-P. and Lian, A. B. 1996)

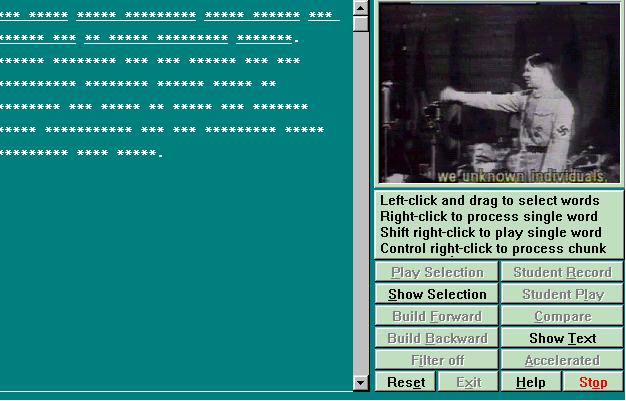

IPF (Intonation Patterns of French) and IPC (Intonation

Patterns of Chinese)

(Lian 1980; Zhang, Lian and Lian 1997)

IPF is based on work theorised originally by the verbo-tonal school of corrective phonetics (Guberina 1972; Renard 1978). The original findings were applied to the systematic teaching and learning of key intonation patterns in French with a view to sensitising learners to the vectors of French intonation and pronunciation as well as improving their comprehension skills (Pegolo 1989).

The approach relies heavily on developing in learners sensitivity to:

These objectives were achieved through the use of a combination of techniques including:

IPC (Intonation Patterns of Chinese) is based on the same principles governing IPF, but must face an additional challenge as the Chinese language not only displays certain vector intonations but it is complicated by its tonal characteristics.

The screen sample shown above displays an exercise requiring learners to discriminate between different electronically-filtered intonation patterns. However, the approach draws on a multitude of different kinds of activities (for further details, cf Lian 1980).

IBMReg (Lian 1984, Lian 1985, Cryle & Lian 1985) is a system which predates MMBrowse by several years and which both raises awareness and reduces processing load. It too was written initially to assist with the development of listening comprehension skills in a foreign/second language although it can be used as a general-purpose delivery system.

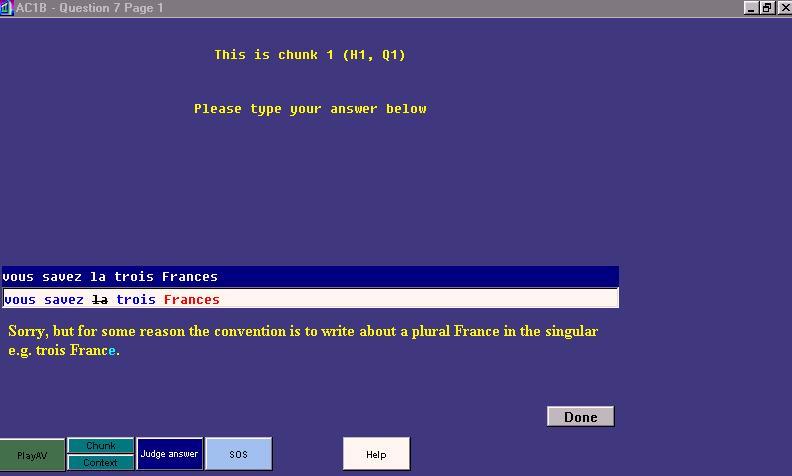

In the first instance, IBMReg was built around a sophisticated answer-evaluation and answer-markup system (cf. Lian 1984) in response to

IBMreg has two phases in its answer-evaluation.

In the first phase, learners’ written responses to a question/task are evaluated against a number of correct answers and a number of predicted wrong answers.

In this case, they think they heard:

The words vous, savez and trois are untouched. They are correct words and are expected in a correct answer. The word Frances is in red. It is now a hotword. The learner has clicked on it and the message at the bottom of the screen has been displayed. As a result, learners’ attention is drawn in a very precise manner to the sequence of characters which requires their attention. The word la has been crossed out. This means that although the word might exist in French (in this case it does), it should simply not appear in the learner’s response. These simple forms of feedback linked to precise character sequences (called answer-markup) enable learners to narrow their field of inferencing, thus effectively lowering their processing load and enabling them to arrive at correct decisions on the basis of their productions rather than on the basis of some pre-determined sequence of steps.

The second phase of answer-evaluation comes into operation after learners have failed to arrive at a correct response within a pre-determined number of attempts. It will not be described here in detail. Suffice it to say that it uses an approach not unlike that of MMBrowse where the letters of each word in the preferred correct response are replaced by stars and the learner is invited to produce more guesses on the basis of the "shape" of the expected response. The answer-markup procedures used in phase 1 remain active.

Further refinement of the answer-evaluation procedure is still possible and will be incorporated in due course. (for further details, cf. Lian 1984; Lian 1985, Cryle & Lian 1985)

The full IBMReg system contained many other features, including recording students’ responses and the time taken to respond to each question.

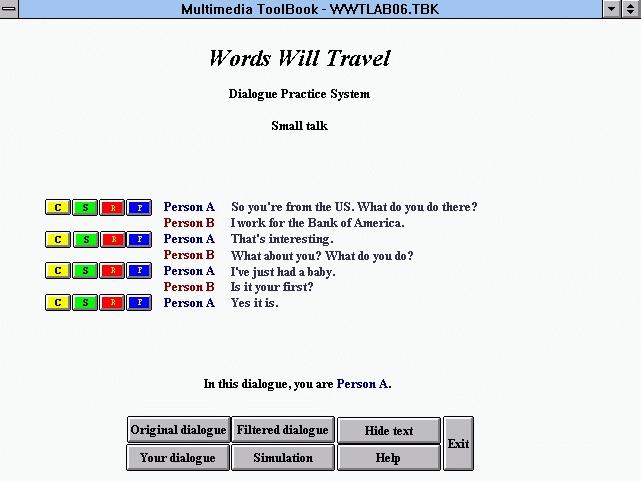

WWTLab: Dialogue practice system (Lian & Lian 1996)

Imagine for instance a situation where, as a learner of English as a second language, it is necessary to make small talk at an Australian party. A likely dialogue is placed on the screen and the learners can take one of the parts. They can rehearse each utterance by listening to it, recording it and comparing it with the native speaker version. They are provided with a digitally-filtered version of each sentence designed to develop their awareness of the intonation patterns involved. They can listen to the whole of the original dialogue as produced by the native speakers.

Next, they can enter a simulation mode where they are able to take one of the roles while respecting the time constraints of natural language interactions. Finally, they can listen to the whole dialogue in which they have just participated. This will give them the opportunity to assess their performance as a participant in the dialogue, enable them to make a critical appraisal of their performances as compared to the various native-speaker models, and eventually alter their productions appropriately.

Communication systems

Valuable as the systems described above might be, they are insufficient.

There needs to be a space where people of like minds who have a need to

communicate can get together to complete the tasks that they have set themselves.

The obvious way for people to meet is in face-to-face mode. But the

developments in new technologies are now producing new opportunities for

persons to meet at a distance and to become acculturated to each others’

communicative systems including, to some extent, their proxemic and kinesic

systems. An environment of this kind is currently under development at

James Cook University by Michelle Kuilboer in the context of her doctoral

dissertation. Her goal is to create a virtual world for language-learning

and for genuine communication in a foreign language (for further details,

cf. Kuilboer 1996).

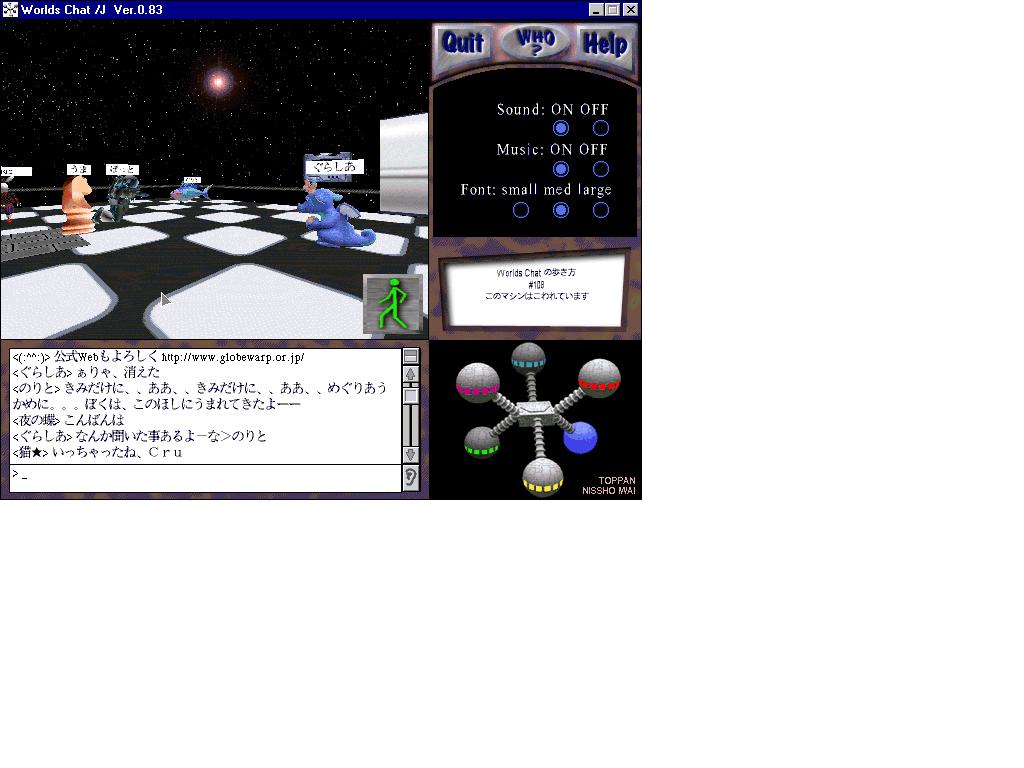

Example screen layout from a Japanese World Chat virtual world

In this Internet virtual world, people function in a graphics-based universe consisting of rooms, buildings, gardens, shops, cafés etc. These virtual spaces provide a venue for real meetings between real people from anywhere in the world who are represented by objects called avatars (graphics objects e.g. a chess piece, a lion, a doll). These avatars can circulate in the virtual world and interact with other avatars. People "talk" to each other by typing messages on the keyboard. The messages can be in any language and can be seen by all (although a private "whisper" mode is available). The image displayed on each person’s screen is meant to represent the view of the virtual world as seen through the eyes of that person’s avatar. Thus the people involved can move about more or less as in a real room. They might choose to move toward each other (respecting or violating proxemic rules) or they might choose to retreat to a corner and observe from a distance: they can simply look if that’s all they want to do. They can also decide to barge into a rowdy group discussion or eavesdrop on an intimate conversation. And they suffer the consequences of their actions as they conform to or break the rules of conduct applying to the group which they have joined. Voice communication is now possible, thus making interaction more "normal" and the playing of music in the background can add to the atmosphere. Video communication will happen in the not too distant future (although as discussed below, that may not be an advantage).

This virtual world contains many of the features of real-life communication, with at least one unexpected advantage: anonymity. As long as video is not used, i.e. as long as the people involved are represented by avatars and cannot actually see each other as they are in real life, the system provides a very high level of psychological protection. Participants can adopt new names, new roles, new personalities. They can change gender, race or nationality. They can be whoever they like and the avatar selected can help them to achieve this by reflecting their new persona. In short, they can take risks that they would not otherwise be able to take while still functioning and interacting in a very real sense with members of the cultural/linguistic group of their choice.

Much experimentation remains to be done with systems such as this to determine their efficacy in giving real people practice in real communication as well as acculturating them to the conventions of a different linguistic community. However, there is good reason for optimism given the obvious success of IRC (Internet Relay Chat) and other "chat" systems (cf. Mathiesen (Lian) 1993) which have existed for several years and which enable thousands of people from all over the world to chat to each other simultaneously at any time of the day or night.

Toward the development of a coherent system

While all the systems described so far appear significantly different

from one another and, indeed, were conceptualised and created independently

of one another over several years, they share at least two important principles:

In order to achieve this, it is proposed to relate the programs to one another as indicated in the diagram below:

Conceptual representation of an integrated

Computer-Enhanced Language-Learning Support System

All lessons and systems described so far in this paper have had their data (i.e. their content) specified at the time at which they were conceptualised. It is now planned to make the programs content-independent. In proper programming style, systems such as WWTLab, Intonation Patterns of French, MMBrowse etc. would contain of a data-free structure specifying how to manipulate information while the information to be processed would be obtained from an external source: the database of authentic audiovisual materials.

In the system conceptualised above, the audiovisual database would act as the central component for all interaction. It would provide information in the usual way, retrieving and displaying information as in the case of the current version of MMBase, but, in addition, it would be able to provide the data or content required by the now "empty" versions of MMBrowse, Intonation Patterns of French, IBMReg and so on.

There are several advantages to this method of organisation, especially in a learner-centred perspective, as the following comments will illustrate.

An additional and significant advantage of such a system is that it can be accessed by learners both locally and remotely via the World Wide Web through the use of Web database management systems such as Cold Fusion used in tandem with streaming audio and video (e.g RealAudio and Realvideo). While transmission speeds across the Internet are still relatively slow, the situation wil certaily improve in the medium term. It is difficult to predict with any precision the likely impact of such a development as it will open up range of possibilities which have not yet been thought of. In practical terms and in the foreseeable future, it will be possible to have data sources anywhere in the world which can be manipulated locally for a variety of purposes. An important practical outcome of this arrangement is that it will be possible to share information across very large distances, to share the preparation load in ways which will make it manageable, ensure that information is always up to date (Lian 1988) and, as a result, to increase substantially the amount of rich information available to learners everywhere.

It will also be possible to provide classroom practitioners with simple tools for entering the necessary information thus increasing the number of people able to contribute to the system as a whole.

The explanations provided so far in relation to the above diagram have referred only to the line headed with the labels "Exercise Generator" and "Retrieval". There remain two other labels: "Materials Generator" and "Systems to be conceptualised: Imagination needed!!".

The Materials Generator label refers to the notion of programming computers in such a way as to generate if not authentic materials, at least "authentic-LIKE" materials. The concept here is to write a computer program with enough information to enable it to piece together, from separate pre-stored components, example interactions between hypothetical human beings in hypothetical life-like situations. The program could produce examples of written language as well as examples of spoken language. Some proof-of-concept systems have already been written and demonstrated and will need to be further developed. For instance, in 1983 Joy and Lian created a dialogue generator illustrating transactions in a German butcher shop. In 1995, Lian and Lian rewrote the software to generate an English version of the same dialogue but with the added advantage of sound and other features of the kind found in WWTLab.

Finally, the label entitled "Systems to be conceptualised: Imagination needed!!" is probably the most important of all. Technology-based systems lend themselves to all kinds of uses and purposes impossible to imagine before their existence. No one can predict what motivated people will think of once they are given the potential to do interesting things. This system is no exception and it will be fascinating and exciting to discover what inventiveness it might trigger.

The future

The description of the systems given in this paper represents only

a beginning. Integrated exploratory language-learning systems of the future

will:

Thus the heart of this system is the theoretical framework which underpins it. This brings us back to the starting-point of the paper: the secret of the Shao-Lin monk.

There is in fact no great mystery. The old monk simply knew how to manipulate the power of socialisation and acculturation to achieve his ends. He operated within an apprenticeship structure: an acculturation framework if ever there was one. He transmitted no knowledge as such to Grasshopper. Instead, he merely challenged his organisation of the world and sharpened his awarenesses. Grasshopper did the rest!

In the context of a (computer-enhanced) language-learning environment it is critical to recognise that functioning in a second language is not realised in the verbalising of relationships between language systems (Bourdieu 1980, p. 97). Learning to function in a second language involves more than just an ability to repeat these verbalisations. It requires mobilisation by the learner of "unspeakable" systems which, once "spoken", i.e. reified, have had stripped from them the reality of the conditions which have contributed to their realisation. The result is that we are no longer dealing with the same systems, even though we may believe that we are.

As pointed out by Ania Lian (adapted from Lian, A. B. 1997, p. 7):

When aspects of this process of relating are singled out for the purpose of their analysis, it is done to help learners in their confrontations with practices in a second language. The help offered, however, is not an explanation of how the wished-for results are acquired. To think so would be to assume that behind an observed regularity exists the reality of its model (Bourdieu 1990, p. 39). To do so, however, is to forget that "the most rigorously rationalized law is never anything more than an act of social magic which works" (Bourdieu 1991, p. 42).

Conceptualised in this manner, methodology directed at attainment of

communicative goals is required to account for individual differences while,

at the same time, seeking ways to reconcile the individualisation prerequisite

with the task of sensitising learners to the systematicities of social

practices or "practical logics" (Bourdieu 1990, p. 92). To simplify this

task would be to fall into the traps of the paradox of communication which

while, on the one hand, it presupposes a common medium, on the other hand,

it makes the medium work only by eliciting and reviving singular, socially

marked and therefore highly personal experiences (Bourdieu 1991, p. 39)."

References

Bourdieu, P., 1991, Language and symbolic power. (Translated by J. B. Thompson) Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Cryle, P. M. and Lian, A. P., 1985, 'Sorry, I'll Play That Again', in Bowden, J. A. and Lichtenstein, S. (eds): Student Control of Learning: Computers in Tertiary Education, Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne, December 1985, pp. 204-213.

Grandin, T. 1996, ‘My Experiences with Visual Thinking, Sensory Problems and Communication Difficulties’, paper published electronically by the Center for the Study of Autism, (http://www.autism.org/temple/visual.html).

Guberina, P., 1972, Restricted bands of frequencies in auditory rehabilitation of deaf. Institute of Phonetics Faculty of Arts, Zagreb.

Hymes, D., 1996, Ethnography, linguistics, narrative inequality. Toward an understanding of voice. Taylor and Francis, London.

Kuilboer, M., 1996, ‘A Rationale for Synchronous Computer-Mediated Communication in an Adult Second Language Classroom’ in The Virtual Classroom: Writing Across the Internet, Berkeley University Press, Berekeley, (in press).

Lantolf, J., 1995, 'Sociocultural theory and second language acquistion', in Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, vol. 15, :pp. 108-124

Lian, A. B., 1996, ‘The management and distribution of language-learning resources in the digital era’, paper presented to the National Conference of the Australian Federation of Modern Language Teachers' Association, Perth, October 1994, published in Scarino, A. (ed.): Equity in Languages Other Than English, Perth, pp. 177-182.

Lian, A. B. 1997, ‘Discourses in conflict: toward an integration of theory and practice.’ Paper read to the Research Seminar in Applied Linguistics, Department of Modern Languages, James Cook University, published electronically (http://sac-exp.jcu.edu.au:8900) - connect to LI5001 and look up under course notes (password required).

Lian, A-P., 1980, Intonation Patterns of French. Teacher's Book. River Seine Publications, Melbourne.

Lian, A-P., 1984, 'Aspects of Answer-Evaluation in Traditional Computer-Assisted Language Learning', in Russell R. M. (ed.): Proceedings of the 2nd CALITE Congress, Brisbane, University of Queensland, pp. 150-160.

Lian, A-P., 1985, 'An Experimental Computer-Assisted Listening Comprehension System', in Revue de Phonétique Appliquée, 73-74-75, 1985, pp. 167-184.

Lian, A-P., 1987, 'Awareness, Autonomy and Achievement'. Revue de Phonétique Appliquée. vol. 82-84, p. 167-184.

Lian, A-P, 1988, 'Distributed Learning Environments and Computer-Enhanced Language Learning', in Dekkers, H. and Kempf, N. (eds.), Computer Technology Serves Distance Education, Rockhampton, Capricornia Institute, p. 83-88.

Lian, A-P., 1994, ‘Dialogue generators Mark II', paper read to the ALAA National Congress, University of Melbourne.

Lian, A-P., 1995, ‘Dialogue generators: the next generation', paper read to the International CALICO symposium, Middlebury College, USA.

Lian, A-P. and Joy, B. K., 1981, 'Verbo-tonalism, Research and Language-learning', in SGAV Newsletter, July Sydney, pp 7-12.

Lian, A-P. and Joy, B. K., 1982, 'Prosody: the Crossroads of Language Systems', in SGAV Review, vol. 1, no. 1, Sydney, pp. 5-11.

Lian, A-P. and Joy, B. K., 1983, 'The Butcher, The Baker, The Candlestick Maker: Some Uses of Dialogue Generators in Computer-Assisted Foreign Language Learning', in Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 60-71.

Lian, A-P., 1993, 'SBPLAY: an audiovisual browser and language laboratory substitute', Chapter 7 in Lian, A-P., Hoven, D. L. and Hudson, T. J.: Audio-Video Computer Enhanced Language Learning and the Development of Listening Comprehension Skills, Australian Second Language Learning Project, pp. 75-92.

Lian, A-P. and Lian, A. B. 1996, ‘Uses of Technology in Language Learning’, Paper Read to session LE2B: Technology in the Language Classroom: Emerging Technologies for Teaching Languages at a Distance NLLIA Language Expo '96 Brisbane

Lian, A-P. and Mestre, M-C., 1983, 'Toward Genuine Individualisation in Language Course Development', in Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 1- 19.

Lian, A-P. and Mestre, M-C., 1985, 'Goal-directed Communicative Interaction and Macrosimulation', in Revue de Phonétique Appliquée, 73-74-75, 1985, pp. 185-210.

Luke, A., 1992, ‘The body literate: discourse and inscription in early literacy training’ in Linguistics and Education, vol.4, :107-129

Mathiesen (Lian), A. B. 1993, ‘Electronic communication media and second language learning’, in ON-Call, vol. 7. no. 3, pp. 15-20.

Pegolo, C. M. 1989, ‘The Role of Rhythm and Intonation in the Silent Reading of French as a Foreign Language’, in SGAV Review, vol. 8, no. 1, April.

Renard, R. 1978, Introduction à la méthode verbo-tonale, Didier, Paris.

Zhang, F. Z. Lian, A-P. and Lian, A. B. 1996, Intonation Patterns of Chinese (in development).